Stories of our past reveal how the lingering injustices of colonisation continue to affect First Nations people in Australia, despite determined efforts to resist and overcome this adversity. The cumulative impacts of invasion – dispossession, displacement and violence that started at first contact, and subsequent policies of control and oppression – have systematically disadvantaged First Nations people, and are still experienced by many people today.

Explore our comprehensive resources to find out more, from broad overviews to in-depth explorations of specific historical eras and firsthand stories from people living with the fallout from this (often very recent) history.

Immerse yourself in stories and articles to understand the connection between our nation’s past and present.

Rotate your phone to see the connection between past and present.

THE PAST

The premise of British colonisation was terra nullius, a legal term which claimed the land (Australia) belonged to no-one. This blatantly denied the existence of First Nations people as human beings (Ross 2006).

THE PRESENT

Terra nullius essentially asserted that First Nations people were non-human. This premise formed the basis of the relationship between First Nations people and the nation state from its very inception. This problematic relationship has never been fully resolved, even in light of the Mabo decision and resulting native title.

THE PAST

Colonial powers never entered into negotiations with First Nations people about the taking of their lands. The lack of treaty or acknowledgement of invasion is one of the key topics in discussions about Constitutional Recognition since 2017 (NITV 2017).

THE PRESENT

The lack of treaty in Australia goes to the very heart of the wound in our nation. Many First Nations people continue to feel the pain of occupation, dispossession and lack of recognition. The absence of a treaty suggests an ongoing denial of the existence, prior occupation and dispossession of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia. It also highlights a lack of engagement and relationship between First Nations and non-Indigenous Australians.

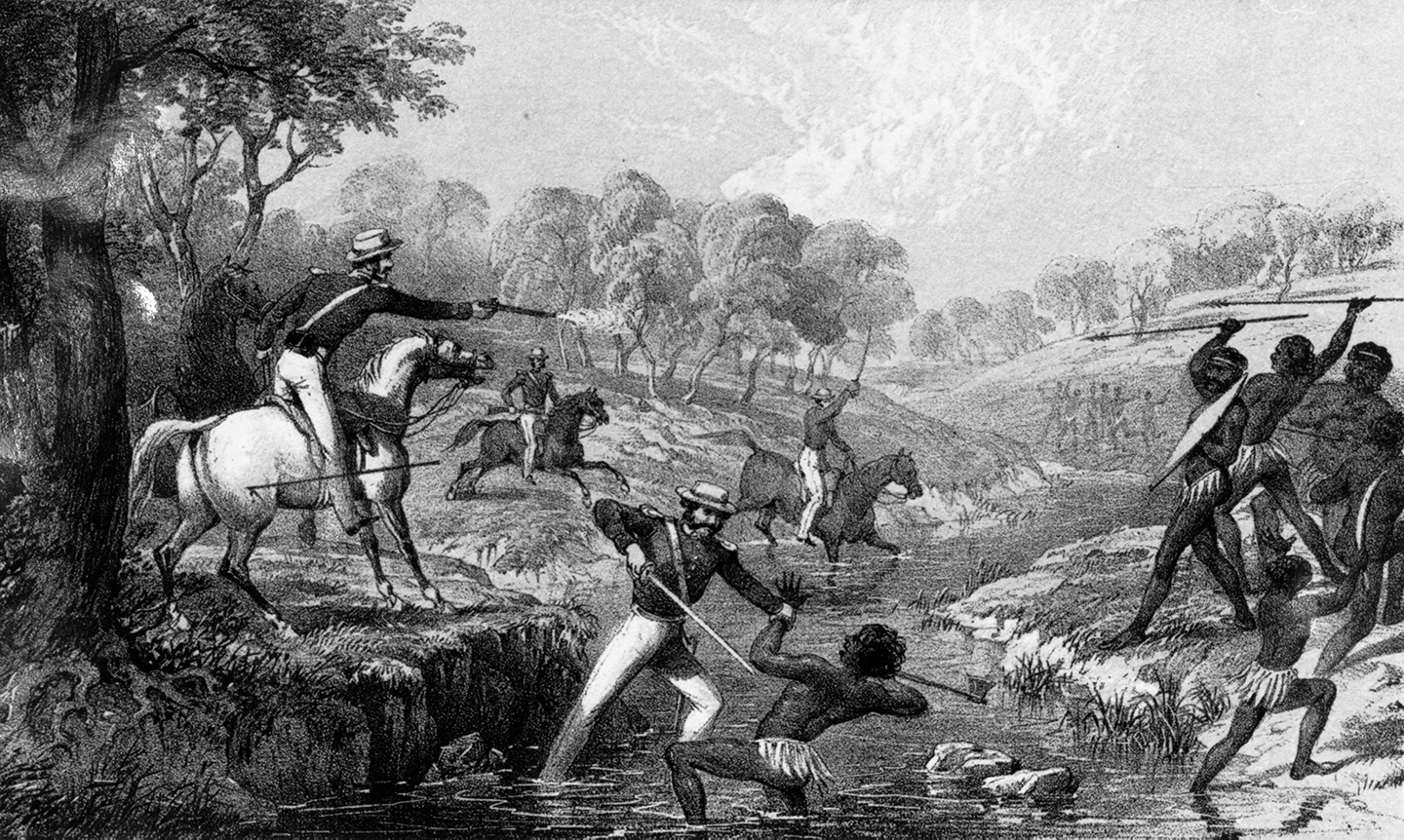

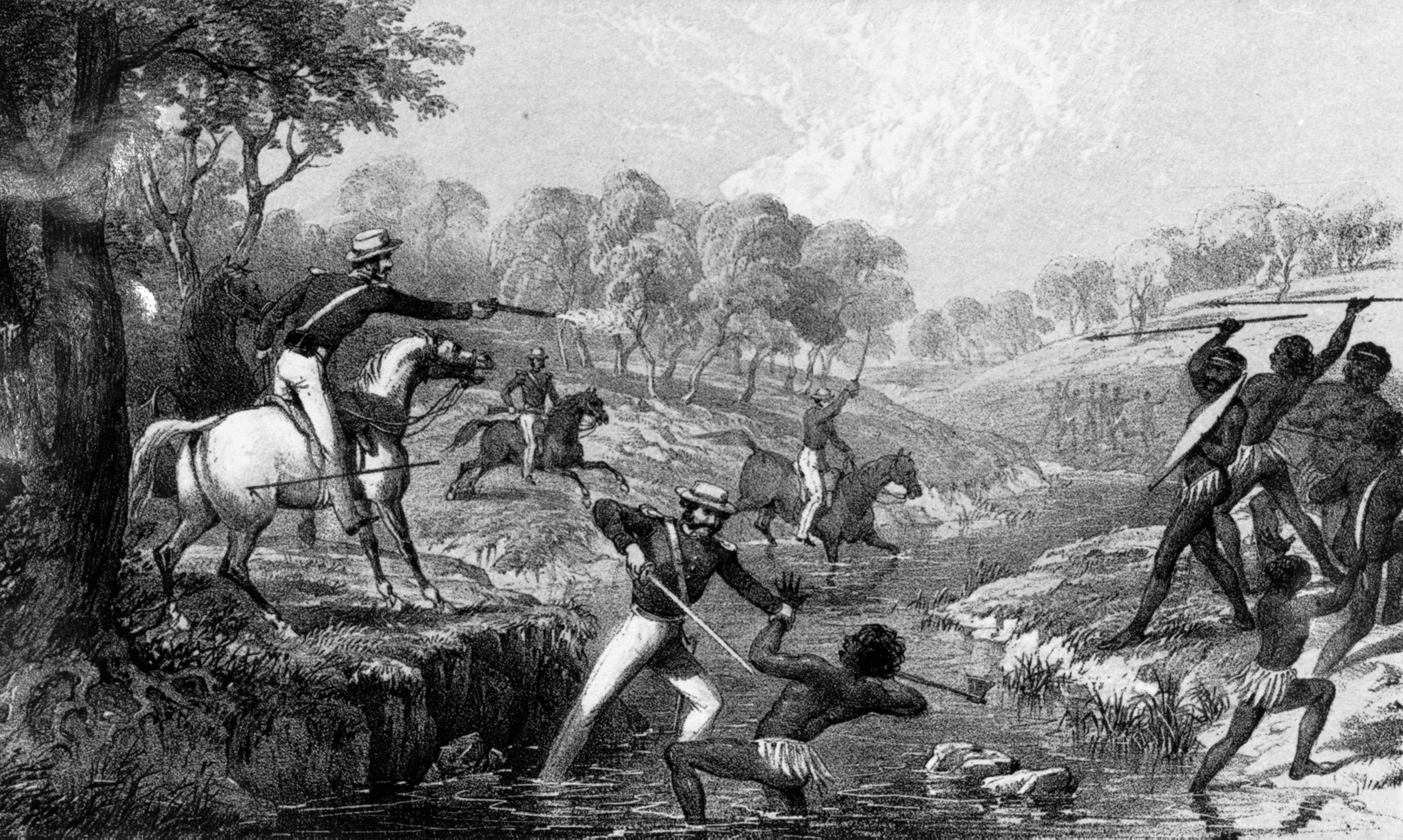

THE PAST

Thousands of First Nations people fought colonisers for their homelands, families and way of life. However, these battles have been omitted from Australia’s war commemoration history (Booth 2017).

THE PRESENT

The omission of resistance wars from history has left most Australians without knowledge of their own history. It represents Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as passive – implying First Nations people didn’t fight for their Country and reinforcing derogatory stereotyping of First Nations people as lazy and incompetent. Through the denial of resistance wars, First Nations people haven’t even been "conceded the dignity due to worthy opponents” (Grey 2008).

The denial of the resistance wars in Australia continues to affect both First Nations people's perception of themselves and the distorted perception many Australians have of our history as a peaceful settlement to be celebrated (Stephens 2014).

THE PAST

Populations were devastated and First Nations people were dehumanised by the colonisers in order to justify the horrific acts against them (Behrendt 2012; University of Newcastle n.d.).

THE PRESENT

The devastation of culture, families and people groups as a result of massacres is still felt today. In many cases, these events resulted in loss of cultural knowledge as entire generations or family groups were murdered. This in turn led to a crisis of identity and belonging for many First Nations people which continues to impact people in the present.

The truth about massacres has been left out of our national history and many Australians are shocked when they come to realise what really happened in towns and places where they now live. The lack of acknowledgement of these events invalidates the experiences and suffering of many First Nations people and is an ongoing source of pain.

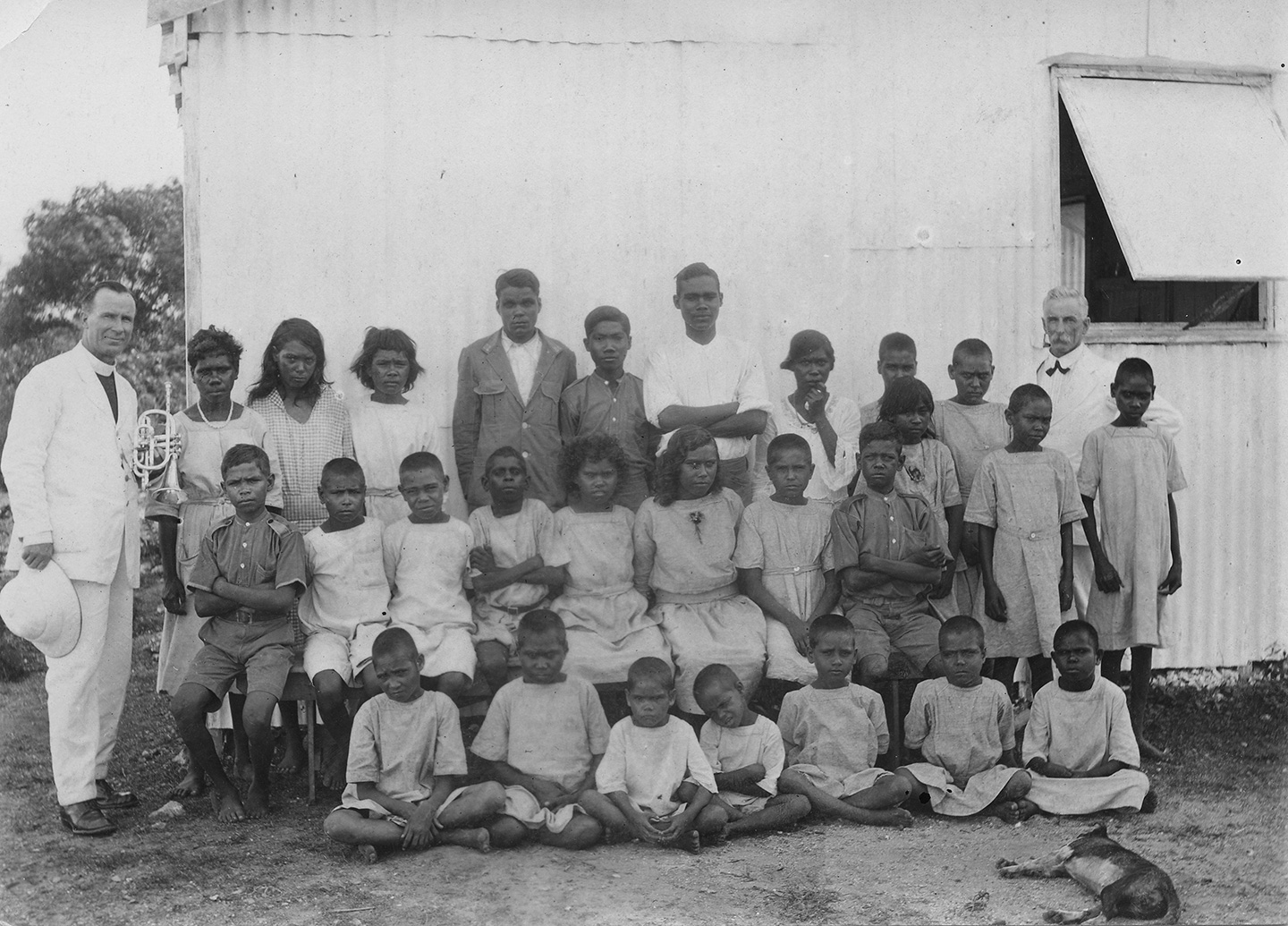

THE PAST

Legislation and state policies served to exclude First Nations people from participation as citizens through their removal from their homes to reserves, missions and cattle stations where their everyday lives were lived under regimes of surveillance control and lack of liberty as equal citizens (HREOC 1997).

THE PRESENT

Today many First Nations people still experience the effects of the missions and reserves. Some people are living with the trauma of growing up in these often abusive environments (HREOC 1997). Other people have been displaced from land and family as a result of the reserve system. Other impacts include intergenerational transmission of poverty as a long-term result of poor nutrition, inadequate education and health care, few assets or a lack of opportunities for previous generations living on missions and reserves.

THE PAST

The forcible removal of First Nations children from their families was part of the policy of assimilation (HREOC 1997). The generations of children removed became known as the Stolen Generations.

Assimilation was based on the assumption of black inferiority and white superiority, which proposed that First Nations people should be allowed to “die out” through a process of natural elimination, or, where possible, should be assimilated into the white community (HREOC 1997).

Children taken from their parents were taught to reject their Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander heritage, and forced to adopt white culture. Children’s names were often changed, and they were forbidden to speak their ancestral languages. Some children were adopted by white families, and many were placed in institutions where abuse and neglect were common (HREOC 1997).

THE PRESENT

The policies of child removal left a legacy of trauma and loss that continues to affect First Nations communities, families and individuals. Research shows that people who experience trauma are more likely to engage in self-destructive behaviours, develop lifestyle diseases and enter and remain in the criminal justice system (Atkinson et al. 2010). In fact, the high rates of poor physical health, mental health problems, addiction, incarceration, domestic violence, self-harm and suicide in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are directly linked to experiences of trauma (Atkinson et al. 2010).

The removal of several generations of children also severely disrupted First Nations cultures, and consequently much cultural knowledge was unable to be passed on.

Many members of the Stolen Generations never experienced living in a healthy family situation, and never learnt parenting skills. In some instances, this has resulted in generations of children raised in state care (HREOC 1997; Atkinson et al. 2010).

THE PAST

From the 1940s, in most parts of Australia, the state governments issued thousands of exemption certificates. They gave First Nations recipients citizenship rights that they otherwise didn’t possess, yet which were enjoyed by the non-Indigenous majority of Australian society. They included ‘privileges’ such as being allowed to open a bank account, receive some Commonwealth social service benefits and own land, and be exempted from the restrictions of state Aboriginal protection laws (HREOC 1997). However, applicants had to agree to abandon association with First Nations communities, give up their Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, including connections with Country, and end contact with their Indigenous kinship, except for their closest family.

Exemption certificates forced many First Nations people to sacrifice their identities in order to obtain a very basic level of freedom enjoyed by other Australian citizens. People with exemption certificates weren’t allowed to enter or stay on Aboriginal reserves and stations, even if they were visiting relatives, which interfered with their family relationships and life. Certificates had to be presented to police officers in order for recipients to be permitted to exist in public spaces, which was also a source of humiliation and shame (Wickes 2010).

THE PRESENT

Exemption certificates contributed to the sense of being a second-rate member of society, as well as the degradation of cultural knowledges. In some cases, this has contributed to a lack of self-esteem and a weakening of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identity that continues to impact generations of First Nations people today (HREOC 1997).

Exemption certificates were related to various policies that regulated and controlled First Nations people and denied full rights and freedoms. These policies have contributed to a legacy of mistrust of authorities in many First Nations families and communities today.

THE PAST

Many First Nations people were exploited for their labour on missions, reserves, cattle stations and as domestic helpers in non-Indigenous homes. Many First Nations people have never been paid wages earned over decades of hard labour (SCLCA 2006). Watch Iris’s story about Stolen Wages here.

THE PRESENT

The non-payment of wages earned has contributed to the transmission of disadvantage across generations and mistrust of authority among many First Nations people.

THE PAST

Since the arrival of the British in the eighteenth century, First Nations people have been marginalised in all aspects of life.

Being denied participation in the mainstream social system meant being denied the rights and privileges of that system. Up until the 1960s, First Nations people were denied access to certain public spaces and were excluded from the national census. Over generations, people were also denied access to health care, education and employment on the basis of their race (Moreton-Robinson 2021).

THE PRESENT

First Nations people remain among the most socially excluded people in Australia (Hunter 2009). Evidence of social exclusion includes current high rates of poverty, incarceration, unemployment, homelessness, poor health and lack of education outcomes.

Past experience of systemic discrimination and prejudice has also resulted in widespread mistrust, anger and resentment towards authorities among First Nations people.

THE PAST

Institutional discrimination happens when a society’s institutions discriminate against a group of people, often through unequal bias or exclusion. This clearly occurred at the beginning of colonisation when First Nations people were “legally” dispossessed and exploited. However, the formal structures and institutions of the time set up a legacy of discrimination against First Nations people. For example, our education, legal and political systems are based on non-Indigenous ways of knowing and operating (individualism, capitalism, private property, the nuclear family, etc.) which often fail to acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander value systems.

There are many examples of how systems established under colonialism continue to marginalise First Nations people. For instance, until recently, land law in Australia was founded on the legal fiction of terra nullius (that this land belonged to no-one at the time of British arrival). In 2017, the Constitution, our nation’s founding document, contains race powers (power to discriminate based on race) and fails to acknowledge the prior occupation and dispossession of First Nations people (Soutphommasane 2015).

THE PRESENT

The ongoing impact of policies and practices that have systematically disadvantaged First Nations people is reflected today in statistics relating to incarceration rates, health, education and politics. While some improvements have been made (such as the 1967 Referendum and recognition of native title) these structures haven’t changed enough to balance or reverse the socio-economic impact of colonisation and past government policies and practices on First Nations people.

THE PAST

From the earliest days, European contact undermined Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander laws, society, culture and beliefs (ALRC 1986).

THE PRESENT

Despite First Nations people’s efforts to maintain and revive cultures in the face of colonisation, there’s no denying that colonisation has deeply impacted Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, societies and languages across Australia. This has had a strong impact on people’s sense of identity and belonging, which bring meaning to a person’s existence. Cultural disconnection and the weakening of identity is the underlying cause of many of the struggles First Nations people are dealing with today.

Australians Together Learning Framework

Take a deep dive into the Learning Framework and explore our vast array of First Nations stories, activities, resources, and more. Curate your own customised learning journey to unlock the truth of our past, prompt reflection about our present, and inspire meaningful action that will bring about a brighter shared future for our nation.

Injustice from the impact of colonisation.

Discover our curated collection of stories, articles and statistics that expose the injustices at the heart of our nation.

Who are Indigenous Australians?

A past that shapes our story as a nation.

Tell stories that many Australians have never heard.

Immerse yourself in stories and articles to understand the connection between our nation’s past and present.

Busting the myth of peaceful settlement

Early missionaries to Australia

The civil rights movement in Australia

What’s it got to do with me?

Examines why this is relevant to every Australian.

Browse articles and stories that explore the ways we’re all connected, and what this means for us as Australians, collectively and individually.

What does this have to do with me?

Australia Day: answers to tricky questions

Everyone has culture. Know about your culture and value the culture of others.

Dive into stories and articles that explore the significance of culture and its role in building a brighter future together.

Welcome to and Acknowledgement of Country

Steps we can take to build a brighter future.

Find inspiration in stories and articles that show even little steps can lead to big change when we do things together.

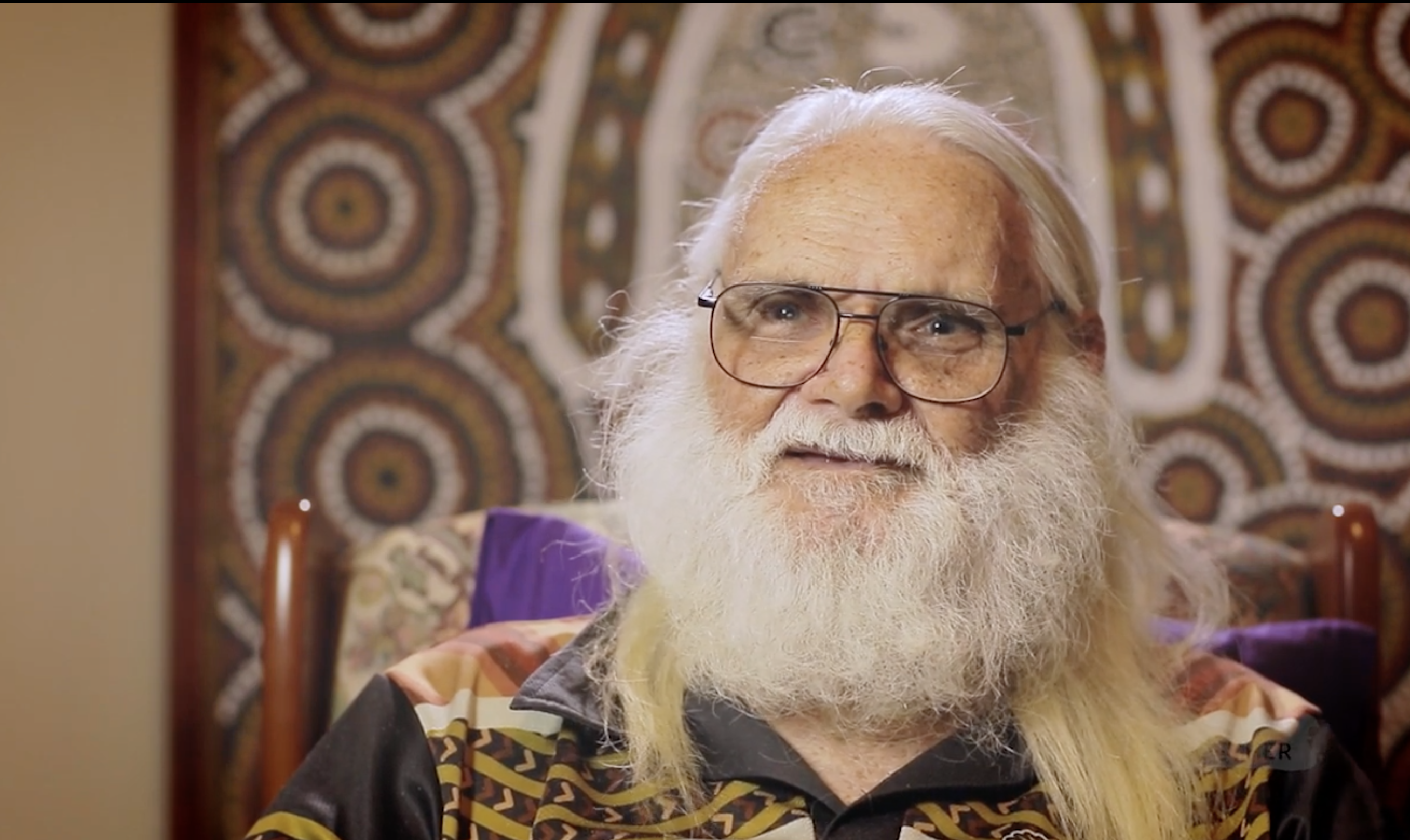

Listen to stories from First Nations people

ALRC (Australian Law Reform Commission) (1986) The Recognition of Aboriginal Customary Laws, (ALRC Report 31), Australian Government, accessed 20 June 2022.

Atkinson J, Nelson J and Atkinson C (2010) ‘Trauma transgenerational transfer and effects on community wellbeing’ in Purdie N, Dudgeon P and Walker R (eds) Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra, ACT.

Australians Together (2021) First Nations disadvantage in Australia, Australians Together website, accessed 20 June 2022.

Behrendt L (2012) Indigenous Australia for Dummies®, Wiley Publishing Australia Pty Ltd, Milton, Queensland, accessed 20 June 2022.

Booth A (17 April 2017) Explainer: What are the Frontier Wars?, National Indigenous Television website, accessed 20 June 2022.

Grey J (2008) A military history of Australia, 3rd edn, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

HREOC (Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission) (1997) Bringing them home: national inquiry into the separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families, The Australian Human Rights Commission website, accessed 20 June 2022.

Hunter B (2009) ‘Indigenous social exclusion: insights and challenges for the concept of social inclusion’, Family Matters, no. 82, Australian Institute of Family Studies, accessed 20 June 2022.

Moreton-Robinson A (5 July 2021) ‘Citizenship, exclusion, and the denial of sovereignty to Indigenous peoples’, ABC, accessed 20 June 2022.

NITV (National Indigenous Television) (6 February 2017) Explainer: What is a Treaty?, NITV website, accessed 20 June 2022.

Ross IJ (October 2006) ‘Aboriginal land rights: a continuing social justice issue’, Australian eJournal of Theology, accessed 20 June 2022.

SCLCA (Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs) (7 December 2006) Unfinished business: Indigenous stolen wages [report], Parliament of Australia website, accessed 20 June 2022.

Soutphommasane T, Lim T, Nelson A and the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) (2015) Freedom from discrimination: report on the 40th anniversary of the Racial Discrimination Act; National Consultation Report, AHRC, accessed 20 June 2022.

Stephens A (7 July 2014) 'Reconciliation means recognising the Frontier Wars’, ABC, accessed 20 June 2022.

The University of Newcastle (n.d.) Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia, 1788–1930, The University of Newcastle website, accessed 20 June 2022.

Wickes J (2010) A study of the ‘lived experience’ of Citizenship amongst Exempted Aboriginal People in regional Queensland, with a focus on the South Burnett region [master’s thesis], University of the Sunshine Coast, accessed 20 June 2022.

The Wound

The Wound

Our History

Our History

Why Me?

Why Me?

Our Cultures

Our Cultures

My Response

My Response